Film Review:

Let Me In–R

Directed by Matt Reeves

Starring: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Chloe Moretz,

Richard Jenkins, Elias Koteas

115 Minutes, Feature Film

Hammer Films

@font-face { font-family: “Times New Roman”; }p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }table.MsoNormalTable { font-size: 10pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

The American film remake sub-genre is, generally speaking, a film industry cop out. Take an inspired (or uninspired) original source–films generally carrying the word “classic” in their notoriety–and present a new and updated version to an audience that studios predict will pay money to see a film they have already seen. While exceptions can be found, most remakes fail to best their source material, the horror genre being the best example.

In the past decade we have seen remakes of more than a dozen universally lauded classics in the horror and thriller genre. Most appeared to be nothing more than opportunities to cash in on a film’s preexisting reputations; seldom did these films shed new light on the classic story. To this end a remake of the 2008 Swedish vampire/coming of age film, “Let the Right One End” seemed pointless and actually offensive to a perfectly fine film that just happens to have subtitles.

Matt Reeves “Let Me In” is a surprisingly rare breed of remakes. Its source material is indeed from foreign soil, which, too, is another sub-genre within the remake sub-genre of horror. Following in the footsteps of such successes as the wave of Japanese ghost story remakes like “The Ring” or “Dark Water,” “Let Me In” hopes to attract a new audience, one not expected to have sat through the subtitles of the original, to this refreshingly unique take on vampire lore.

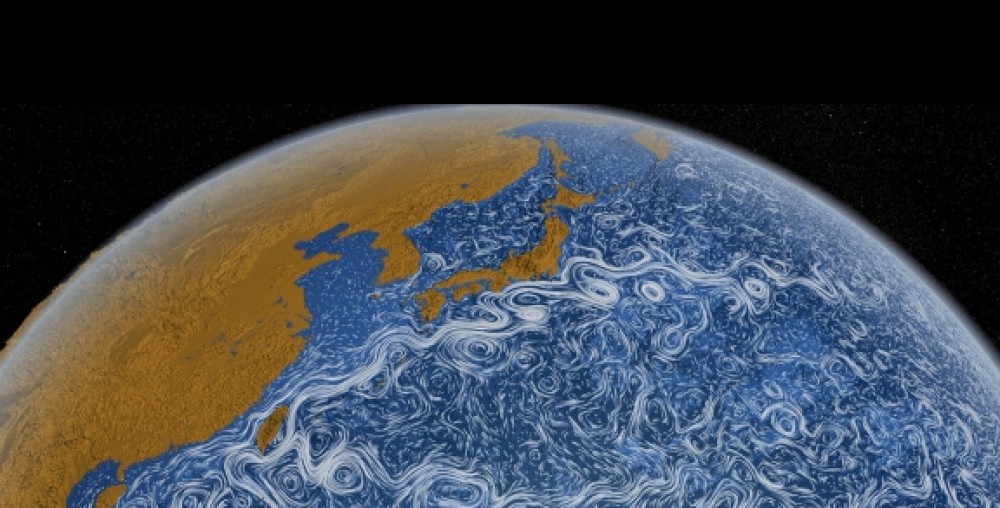

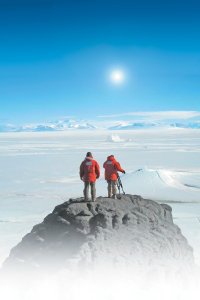

It’s also a rare breed of remakes in that scene for scene “Let Me In” is almost a direct retelling of its predecessor. Its flow is uniform as are many of the original’s memorable shots. Like its source material, “Let Me In” is set in a cold, empty place (here, Los Alamos, New Mexico, filling in for the desolate suburb of Stockholm). It’s an understandably bleak environment for what on the surface is a terribly bleak story, one that has climaxes that are both triumphant and despairing.

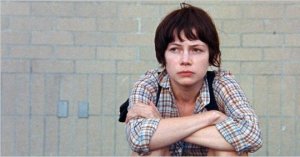

Owen (“The Road’s” Kodi Smit-McPhee) is a young, lonely and bored boy. He spends his days fleeing from bullies; avoiding his overly preachy, wine-o mother; spying on neighbors through his apartment’s very own “rear window;” and indulging in the one thing that seems to bring him comfort, his Now & Later fruit chews.

When a young and mysterious girl named Abby (Chloe Moretz) arrives one frigid night observed walking barefoot through the snowy courtyard, Owen’s world suddenly becomes all the more interesting.

The friendship that forms is the essence of what makes this story (the original was based off a best-selling Swedish vampire novel) so unprecedented in vampire iconography. This isn’t the 90201-themed love triangle of the “Twilight” series, nor does it attempt to be a clever comment on society a la HBO’s breakout hit series, “True Blood.”

“Let Me In” is a love story like “Harold and Maude” is a love story. It is a coming of age story in the same austere way Cormac McCarthy’s apocalyptic novel, “The Road” is. More to the point, it doesn’t glamorize the vampire lifestyle, but rather shows it as a cruel infliction on everyone involved, both physically and mentally.

While some alterations are made from “Let the Right One In” (a strange scene from the original involving a pack of wild cats is smartly removed this time around) the filmmakers respectfully mirror the original, swapping for a Reagan era small town U.S.A setting and throwing a larger budget to the production (a particularly effective shot from the back of a car as it slides out of control stands out).

While some alterations are made from “Let the Right One In” (a strange scene from the original involving a pack of wild cats is smartly removed this time around) the filmmakers respectfully mirror the original, swapping for a Reagan era small town U.S.A setting and throwing a larger budget to the production (a particularly effective shot from the back of a car as it slides out of control stands out).

Director Matt Reeves drops snippets of Reagan’s famous, “Evil Empire” speech early on in the film, a speech in which the former President acknowledges evil’s existence in the world. This is not merely a way to present the setting. Whether or not the characters believe or know there is definite evil in the world is beside the point; they don’t understand it. In “Let Me In” things aren’t as black and white as good and evil.

Religion is hinted at throughout the film, primarily with the word evil being tossed around. Owen’s mother is hardly seen or heard from in this film because she is not entirely there for her son. She is struggling with her own beliefs and her weakness for the bottle. She sees and believes in the evils of the world but yet doesn’t care enough to protect her own son who ultimately turns to violent acts to solve his own confrontations with the evil that hears about but doesn’t quite understand.

We see early on where his character is headed in terms of his budding kinship to Abby who, as she puts it so eloquently, has been twelve years old for a very long time. To say much more would spoil the film’s intrigue. To tread lightly, this is a film that leaves the viewer wondering about the decisions made by its characters after the credits roll.

“Let Me In” features a stellar cast including the great character actors Elias Koteas (“The Thin Red Line”) as a curious, soft spoken policeman, and Richard Jenkins (HBO’s “Six Feet Under”) as Abby’s mysterious father-like caretaker. Here both men play somber and serious men who don’t quite understand what is happening around them, but are drawn into the fold nevertheless. In one scene Jenkin’s protector character pleads with Abby not to see Owen again. It’s a simple exchange of words that manages to tell so much about his past with her and his understanding that after he’s gone she will still be.

“Let the Right One In” is a masterful little horror film that should be seen by all fans of the genre. On its own, “Let Me In” stands up surprisingly well but ultimately feels like an easy way around trying one’s hand at a foreign language film. It’s a far more insightful film than anything else you might see this Halloween season and hopefully will pique the curiosity of its viewers enough to seek out the original.